Censorship of Children’s and Young Adult Literature

I would like to begin this section with some brief definitions that come from a few sources: the NCAC and Henry Reichman’s work Censorship and Selection: Issues and Answers for Schools. Reichman formally defines censorship as “the removal, suppression, or restricted circulation of literary, artistic, or educational materials – of images, ideas, and information – on the grounds that these are morally or otherwise objectionable in light of standards applied by the censor” (Reichman 2). In layman’s words he follows up with “censorship is simply a matter of someone saying: ‘No, you cannot read that magazine or book or see that film or videotape – because I don’t like it’” (Reichman 3). The NCAC employs a set of expectations for libraries, both school and public, administrators and parental community to consider when a work or material becomes an issue: “Censorship demands require educators to balance First Amendment obligations and principles against other concerns – such as maintaining the integrity of the educational program, meeting state education requirements, respecting the judgments of professional staff, and addressing deeply held beliefs in students and members of the community.”

Throughout this section, I would like to attempt to balance and question selection processes in accordance with NCAC recommendations. How as a public librarian does one maintain ethical practice in the face of emotionally charged challenges? How as school librarians does one balance out educational goals vis-a-vis parental angst? Answers to these questions will in some way make their way into the lecture. And some questions will be left for the reader to wrestle with.

Examples of Politically Motivated Censorship of Young Adult Works

The Politics of War and Perspective: Vietnam War

Reichman lists several examples of censorship that come from a political perspective. He documents such political censorship that stems from “objectionable brothel scenes” in a 1974 Vietnam War film, Hearts and Minds. A teacher refused to edit out the brothel scene and then the principal banned the resource (Reichman 46). Upon viewing the documentary, the film consists of a collection of clips and interviews from the politicians involved in the lead up into the Vietnam War. The documentary also includes clips of actual war footage; people being shot and blown up, dead bodies on display, and Hollywood war musicals.

The brothel scene, however, is the bone of contention with this political resource that leads to the censoring of legitimate commentary on war. The brothel scene is, to me, highly disturbing content for any high school classroom. The graphic nature of the brothel scene coupled with the unapologetically profound lack of compassion for the sex workers from the soldiers and the camera crew filming the documentary, (my personal opinion), bring legitimate questions of classroom suitability, and thereby, the challenge to this documentary. After viewing the full documentary on Youtube, (the brothel scene appears at 45 mins and lasts 2-3 minutes of the two hours), many educators might not even lift an eyebrow over the documentary’s removal from the classroom and complete censorship. Others may have justifiable opposition to this censorship decision.

The question of political censorship is still on the table, however. IMDB describes Hearts and Minds as “a documentary of the conflicting attitudes of the opponents of the Vietnam War.” The review goes on with such superlatives as “startling”, “courageous”, “powerfully affecting”, “explosive”, “persuasive” and “the winner of the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1975.” Based on this lavish description, the documentary would seem to offer sound educational value to a classroom that the students in this instance did not get to hear, view or debate. Was the challenge and ultimate censorship motivated by the political perspectives offered in the documentary, and the brothel scene was manipulatively used to legitimize its removal? If so, then this censorship was politically motivated. If this documentary was censored for its sexual content, then I disagree with Reichman in his statement that this censorship stems from political pressure.

A reader needs to keep in mind who purchased this material, (the library? the educator? the humanities department?) and again, what criteria are put forward to school staff and librarians regarding curriculum materials. A school library that houses such a documentary surely has supplemented the humanities department with such a purchase. The “conflicting attitudes” noted in the film are from the French perspective and the American perspective leading up to the war. This film seems to get at the heart of educational pursuits, which include the discussion of historical perspectives. My question to my classmates is what step would you take if this documentary were requested for purchase in a public library or a school library? Is refusing to purchase this documentary for the school library to avoid parental “pressure” an act of censorship? Is it ok to keep this in the library for checking out, but the educator can’t show the work to the students in a classroom setting?

The Politics of Gun Control

An Illinois community debated the controversy of gun control. The principal, after the debate, elected to remove Guns and Ammo from the school library (Reichman 45). This is a high school library, so one has to question whether a periodical that celebrates guns, Guns and Ammo, is even appropriate for a high school audience. However, if the school librarian looks to the online Guns and Ammo website page, the “About” page identifies Guns and Ammo as a sporting enthusiast magazine, replete with outdoor nature settings. By the Guns and AmmoMedia Kit definitions, this magazine is about sports, which are not limited to hunting, but include fishing, bow and arrow skills, and general outdoor living. Based on the definition provided by the magazine, these topics are age appropriate for high school students. The politically motivated removal, post-Columbine, can lead a school administrator to make a censorial choice for the right reason. In the balancing act between providing diversity of materials in the library and attempting to instill within students non-violent methods of resolving conflict, the magazine, Guns and Ammo, raises a political point of friction.

Should schools consider political climate in their purchases? Should the recent history of school violence – consider Sandy Hook – impact school library selection? And who determines this selection criteria in the light of political events? Do shifting political climates mean shifting purchasing criteria? Do public libraries face the same challenges as school libraries?

Being Green is Political: Ecological & Environmental Clashes with the Logging Industry

In an Oregon community, two texts came under fire. Both The Lorax by Dr. Seuss and Eli’s Songsby Monte Killingsworth were respectively labeled as being “hostil[e] to the timber industry” and “logger-bashing” (Reichman 45). Eli’s Songs narrates the story of a twelve year old boy who falls in love with the magnificent trees of a nearby forest and tries to prevent their imminent destruction. These last two political examples of censorship were more “pressures” (Reichman 45) and NOT censorship. Neither of the children and YA books were removed from the library, but the emphasis that Reichman makes here is that a political environment can motivate not only pressure to censor, but actual self-censorship in the selection process to avoid challenge from parental communities.

Eli’s Songs, albeit age appropriate for middle school aged children again continues to force the question about selection and criteria. This young adult literature selection is identified by Kirkus Reviews as age appropriate for 11-14. More school librarians and middle school educators could easily defend this book in its curriculum. According to Kirkus Reviews, “the author leans hard on Oregonians for their narrow-mindedness” (KR), but the responsibility of the school library and of the educator is to explore perspectives, so when pressure from the community mounts, what choice should the librarian make regarding selection and purchasing? Is moving a book from one section to another a concession or an act of censorship? (On some campuses, the library houses middle and high school works in the same location).

The Politics of Language:

Reichman is not the only observer of censorship history to address a community’s desire to purge unsavory language from the eyes and ears of their children. Reichman cautions the school library or school administration against embracing a selection policy whereby profanity is the measuring stick for appropriateness (47). Reichman studies at length how often libraries deal with challenges based on “dirty” words. He writes that “a frequent objection…against library books is that they use ‘inappropriate’ language or [use] even ‘obscene’ or ‘pornographic’” (46) language.

The book Snow Bound by Harry Mazer received a challenge whereby the “parents…asked that the book be ‘withdrawn from all students’ because of several profane oaths, two four-letter words for bodily wastes, and use of the terms ‘crazy bitch’ and ‘stupid female’ by a character” (Reichman 47). Amazon shares the publisher’s blurb for this young adult novel. The fifteen year old protagonist, Tony Laporte, is portrayed as a “spoiled” kid who in a huff of anger over not getting his way, takes off with his parents’ car. This synopsis clearly establishes a tone about character. The ideas for a library to consider would have to include whether the profanity is cheap titillation on the author’s part or whether the profanity is an accurate voice of a spoiled kid who throws tantrums when he doesn’t get his way. In this tension, language becomes political.

This consideration of voice of a character appears in another more recently challenged and censored book based on “dirty words”: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. Just as Tony Laporte engages in unsavory language, so too does Arnold Spirit Jr. from Part-Time Indian. Reichman argues that a school library policy should not include sending notifications to a parental community about new purchases for the library and which books include profanity. Reichman defends a policy that “states explicitly that materials containing profanity ‘shall be subjected to a test of merit and suitability’” (Reichman 47). What this test includes, Reichman does not develop, but given that the direction of a fictional character’s development, and the tone or mood of a children’s novel or young adult novel all stem from the language, would tone or voice be a part of that merit and suitability test?

Click here to see Sherman Alexie’s response to censorship.

An obvious dodge is left out of this “dirty word” discussion. A cultural context exists in America that includes racial epithets. Some school communities will voice complaint with Huckleberry Finn based on the frequent use of the N-word and other communities will not voice any complaint about this same text at all. The test of “merit and suitability” falls short here if there isn’t an elaboration on what is suitable in terms of language in respect to cultural context. Surely a request to remove Part-Time Indian because of “dirty words” should not measure short in comparison to To Kill a Mockingbird with its multiple uses of racial epithets. Cultural context needs examination, and a recognition that Harper Lee captured the voice of the Jim Crow South, just as Sherman Alexie captured the voice of a young teenaged boy grappling with poverty on a reservation.

Lastly, The Bridge to Terabithia received a challenge based on “dirty words” as well: “one Lincoln Nebraska parent protest[ed] the use of the words ‘lord’, ‘damn’, ‘snotty’, and ‘shut up’” (Reichman 48). The novel remained in the library. The author of the 1977 novel, Katherine Paterson, responds to School Library Journal reviews in such a way that makes one question if the parents who complained about the text actually read the ideas presented in the novel as opposed to only reading the specific words, two very different purposes. Paterson writes: “The time a child needs a book about life’s dark passages is before he or she has had to experience them. We need practice with loss, rehearsal for grieving, just as we need preparation for decision making” (SLJ). These are large and complex ideas for young adults to tackle, and certainly the conversation of language can be part of that discourse, but which concepts most need addressing: appropriate language of the authors or the conflicts and ideas from which the protagonists must conquer or endure within the novel? Is this question part of a selection criteria?

Based on all the exemplars of what should or should not enter a library makes for a harrowing selection criteria, and yet in spite of my frustration with a vague definition for selection criteria, is it best that the test of suitability is general and unspecific? If so, how is this best? Further to this, does a school librarian or school selection committee need to define what is profane? Is ‘shut up’ profane, just as the N-word is profane? The challenge that the school librarian encounters in defining a selection criteria in the face of social issues, parental concerns and political climate is certainly daunting. If selection criteria for school and public libraries should be different, how so?

The Politics of Sexuality: A Question of Morality and Reality

Young Adult Books and Children’s Books

No conversation about censorship is complete until Judy Blume’s novel, Forever, is addressed. In the case Reichman delineates regarding Blume’s novel, Forever, censorship did not occur in a Wisconsin community school. Reichman documents the attempt to ban Forever from the school library noting “six people who…[spoke] for its removal” (Reichman 52) and “41…to defend its selection” (Reichman 52). Kirkus Reviews offers a mild rebuke about the sexuality, but frames Blume’s work as lacking depth, whereas School Library Journal frames the novel in more empowering tones, neglecting the very specific sexuality included in the novel. One SLJ reviewer writes: “[Cath and Michael’s ]relationship is unique: sincere, intense, and fun all at the same time.” Note that no reference to sexuality appears in the review. In spite of one of these reviews being less than favorable, neither really touches on the pronounced sexual development of the female protagonist. For these frank and bold sexual matters, Judy Blume has had several of her works challenged and banned: Forever, Blubber, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, Deenie, Tiger Eyes, and Then Again, Maybe I Won’t. Blume penned all of these novels “between 1971 and 1980” (Miller 43) and all of these novels “reside on the American Library Association’s List of 100 Frequently Most Challenged Books” (Miller 45).

Pat Scales addresses an interesting criticism of how books of a “mature” nature end up in the hands of readers who are too young. Scales identifies that one factor in this crisis between parents’ concern for what children read and what libraries can select stems from computer programs that “determine the readability level of children and of books” (Scales 534), but then those same programs do not account for the maturity of the student, (or lack thereof), selecting the material based on reading level. Just because the third grade student can read at sixth grade level does not mean the student is mature enough to read the content of a sixth grade level text. This friction between capability and maturation is where Scales identifies one factor leading to challenge in the library. The scenario Scales presents is of the third grade aged student going home with a book intended for a more mature reader, scandalizing the parents and prompting backlash.

An article from American Libraries documents the controversial trajectory of banning Blume’s novel, Forever. When challenges occur, schools have a reconsideration committee, and typically, at this point in the challenge process the committee has the final say, as per an established policy. A Mediapolis School District in Iowa, however, clearly had an appeal go beyond the reconsideration committee to the school board whereby the reconsideration committee’s decision was overturned because Forever “does not promote abstinence and monogamous relationships [and] lacks any aesthetic, literary, or social value” (Board 390). The board removed the book from the library.

The NCAC’s rebuttal to this type of usurpation, however, is clear. Overturning the reconsideration committee’s decision and pulling Forever from the school library is censorship, but further to that, comes the dangerous establishment of nullifying the purpose of a selection committee and nullifying the purpose of a reconsideration committee, as well as nullifying any or all established policies regarding criteria for selection or reconsideration. All a parent has to do is go to the board to undermine policy. The NCAC responds to this type of usurpation with the following: “Access to a wide range of views and the opportunity to discuss and dissent are all essential to education and serve the schools’ legitimate goals to prepare students with different needs and beliefs for adulthood and participation in the democratic process.” Usurping the selection process and the reconsider committee both functions antithetically to school mission statements, particularly those mission statements that want students to grow into successful democratic citizens. How can schools expect students to develop into citizens who ask questions when the actions of debate and dissent are usurped and taken from them? Students will not develop what they don’t practice, and in this case, it’s a citizen with the ability to read, to inquire, and to debate. Should not student voices matter in what young adults and children want to read?

Young Adult Magazines:

Reichman moves his examination of censorship of young adult texts to periodicals suited to young adult readers in school libraries. According to Reichman, a review committee decided the periodical materials (Seventeen, YM, and TeenMagazine) were age appropriate for Middle School, but the school superintendent overruled the policy decision. Again, a usurpation of selection and reconsideration occur. Given the enormous shift in advertising and the pronounced inclusion of sexualized images or sexual topics, what should a selection committee consider when purchasing periodicals for its library, particularly periodicals targeted to young adults?

The online website for Seventeen magazine promotes itself to a young adult audience from ages thirteen to college age students. In fact, one page is dedicated to university stories, the stress inducing application process, and also features an article addressing the new California law allowing students under the age of eighteen to “erase” their online footprint. Hall’s Seventeen article connotes the type of magazine that targets thinking young academic ladies who are aware of how choices can come back to haunt them. In other words, based on the article’s presence in the online edition of Seventeen, their target demographic is not only young girls interested in beauty tips and prom tips, but an audience of critical thinkers as well.

This rebuttal to sexual content concerns, however, may not persuade emotional families who simply want to protect their children from sexualized articles and advertisements that do appear in the print edition of Seventeen. But the controversial problem that may arise from a banning of the physical magazine is what to do regarding students’ internet access to the same magazine. Does the school then impose stricter filters to censor access to Seventeen’s online edition in order to keep with the spirit of banning the print edition?

So what are the solutions to challenge, usurpation of reconsideration committees, and selection? What selection and reconsideration practices occur in your libraries?

Steps for Success:

The NCAC website offers a censorship toolkit targeted to libraries in the k-12 educational domain. The toolkit covers some of the most frequent reasons a work is challenged and strategies to address the challenges. A careful step-by-step challenge process for the challenger is documented, and the most salient point of the challenge procedure is that the “Complainants must have read/seen the entire work objected to” (NCAC). Reichman and other critics note how often challenges to books and other library materials come from a complainant who has not even read the work in its entirety.

I hope these discussion questions prompt careful consideration and that the recommendations for selection and reconsideration are fruitful in your own domains.

Works Cited

Bird, Elizabeth. “Top 100 Children’s Novels Poll #10: Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson.” School Library Journal. 16 June, 2012. www.blogs.slj.com. 20 April, 2014.

Blume, Judy. “1996 Margaret A. Edwards Award Acceptance Speech.” Journal Of Youth Services In Libraries 10.(1997): 148-156. Library Literature & Information ScienceFull Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 19 Apr. 2014.

“Board Pulls Blume’s Forever.” American Libraries 25.5 (1994): 390. Academic Search Complete. Web. 19 Apr. 2014.

Chen, Diane. “Practically Paradise: Top Teen Titles.” School Library Journal. 20 June, 2010. www.blogs.slj.com. 19 April, 2014.

Hall, Macy. “New Law Allows You to Delete Your Digital Disasters.” Seventeen. 2014. www.seventeen.com. 20 April, 2014.

Miller, Joanna. “Judged Judy.” Bitch Magazine: Feminist Response To Pop Culture 46 (2010): 46-50. Academic Search Complete. web. 19 Apr. 2014.

“Book Censorship Toolkit.” NCAC. New York, NY. 2014.www.ncac.org. 20 April, 2014. http://ncac.org/resource/censorship-tools-du-jour/.

“News for Hearts and Minds (1974).” IMDB. 2014. www.imdb.com. 20 April, 2014.

Reichman, Henry; American Library Association. Censorship and Selection: Issues and Answers for Schools. Chicago, IL, USA: ALA Editions, 2001, p.2

“Review of Forever.” Kirkus Reviews. Oct. 15th, 2011. http://www.kirkusreviews.com. 20 April, 2014.

“Review of Eli’s Song.” Kirkus Reviews. 20 May, 2010. www.kirkusreviews.com. 20 April, 2014.

Scales, Pat. “What Makes A Good Banned Book?.” Horn Book Magazine 85.5 (2009): 533-536. Academic Search Complete. Web. 19 Apr. 2014.

Vang, Sao. Hearts and Minds (1974). Youtube. 22 August, 2012. www.youtube.com. 19 April, 2014.

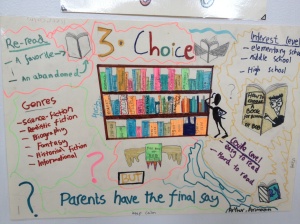

Students will have the choice to read anything they want.

Continue reading →